Published on

The ear, a complex functioning

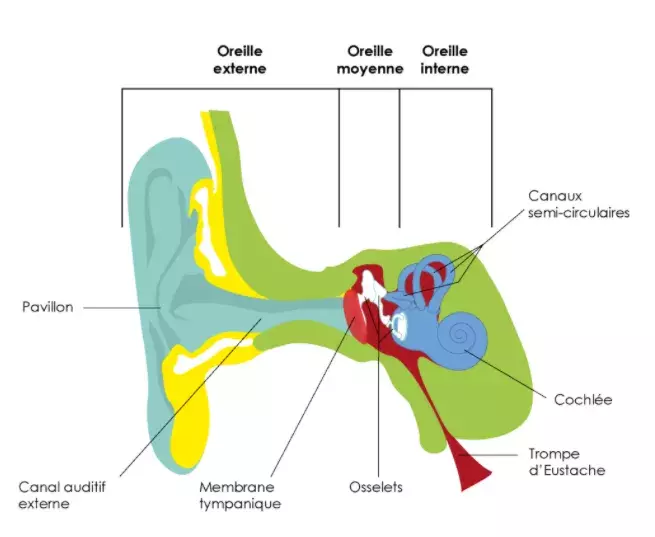

Our ears are made up of three main parts: the outer ear, which contains the ear canal, the middle ear, which amplifies sound, and the inner ear, which plays a major role in our hearing and balance.

The cochlea and vestibule, both located in our inner ear, contain sensory cells that pick up sound vibrations from the outside and transform them into electrical signals. As they pass through the auditory nerves, the electrical signals produced by the sensory cells in the cochlea are then processed by the brain as sounds and that is how we hear.

Damage to any of these parts of the ear can cause different forms of hearing loss of varying severity.

Not one, but several genetic deafness

Deafness can be divided into three main categories:

- Conductive deafnesss related to damage to the outer and/or middle ear.

- Perceptive or neurosensory deafness, related to the cochlea, and/or the auditory nerve pathways, and/or the central structures of hearing.

- Mixed deafness, combining these two components.

80% of early deafness not related to ear infections are genetic in origin. Hearing loss can exist from birth or appear later in life until adulthood.

"It can be difficult to identify the genetic causes of deafness because abnormalities in several different genes can lead to the same type of deafness, whereas identical genes can cause different deafness depending on how they are altered: a mutation in a gene can, for example, cause isolated (non-syndromic) deafness, whereas another mutation in the same gene can cause syndromic deafness, i.e. accompanied by other symptoms," explains Sylvain Ernest, a researcher at Institut Imagine.

Approximately 200 genes responsible for non-syndromic deafness have been discovered to date, and 500 syndromic deafnesses have been described, which may be associated with kidney, eye, neurological and cardiac disorders in particular.

For more information on deafness, reference centers, care, patient associations, go to the site of the rare diseases expertise platform of Hôpital Necker-Enfants malades AP-HP and Filière SensGène.

Genetic deafness research at Institut Imagine

At Institut Imagine, a research and care team is dedicated to understanding and treating genetic deafness. Within the Embryology and Genetics of Malformations Laboratory, directed by Jeanne Amiel, the research of Dr. Sandrine Marlin and researcher Sylvain Ernest is specialized on congenital deafness, i.e. deafness appearing at birth or early childhood. They study neurosensory deafness, deafness with malformations as well as syndromic deafness. This research has made it possible to identify several genes involved in these deafnesses - new genes or new mutations in genes already known to cause deafness - and to identify their mechanisms.

Institut Imagine is working in close collaboration with Hôpital Necker-Enfants malades AP-HP and the genetic deafness reference center directed by Dr. Sandrine Marlin. These close ties enable patients and their families to benefit from scientific advances.

Learn more about the journey of patients with genetic deafness and research.